1994, on our own four feet

1994, on our own four feet At the end of my father's life, when I was getting to know him in new ways, he spent all day in bed. Before that, he got around in a wheelchair. And when I say got around, he really got around. He took the bus everywhere and was happy doing so, even when that meant taking 3 buses and having to choose stops based on sidewalks and curb cuts (which don't exist everywhere in Seattle).

Independence was very important to Dad. He frequently left himself voice memos, some of which were affirmations: "I travel around the city by myself on the bus. I am good at that," and "I do family bookkeeping. Also I am good at maneuvering my wheelchair." When well-meaning people would push his electric-assisted wheelchair without asking, he bristled. A wheelchair is personal, an extension of the body, and even medical personnel sometimes fail to recognize that.

Before the wheelchair there were arm crutches, the kind with cuffs that go around the forearms, and before that, a cane. He was walking with a cane at my wedding, and when we danced together, he felt steady and light on his feet.

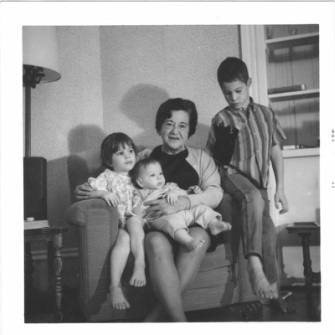

It's hard for me to cast my mind back before concerns about his health became central to my life. Certainly, there were big chunks of time when he wasn't doing so well and I wasn't aware of it. While my attention was focused on him at the end of his life, I need to remind myself that there was a time when he was active in the outdoors, taking bike-camping trips and hiking the beautiful Pacific Northwest woods.

I liked dancing with him at my wedding. It seemed symbolic, traditional, a ritual that signified my participation in some ancient customs of transition. Like the transition from my father's home to my husband's home, which in my case was pure symbol, since I'd only lived with Dad a total of about a year from the time I was 4 and my parents divorced. My struggle between wanting to see myself as a rebel and wanting to embrace what little tradition and ritual I can goes on. Yet MY dance with MY father at MY wedding felt personal and right, and I'm glad he was able to share it with me.

Independence was very important to Dad. He frequently left himself voice memos, some of which were affirmations: "I travel around the city by myself on the bus. I am good at that," and "I do family bookkeeping. Also I am good at maneuvering my wheelchair." When well-meaning people would push his electric-assisted wheelchair without asking, he bristled. A wheelchair is personal, an extension of the body, and even medical personnel sometimes fail to recognize that.

Before the wheelchair there were arm crutches, the kind with cuffs that go around the forearms, and before that, a cane. He was walking with a cane at my wedding, and when we danced together, he felt steady and light on his feet.

It's hard for me to cast my mind back before concerns about his health became central to my life. Certainly, there were big chunks of time when he wasn't doing so well and I wasn't aware of it. While my attention was focused on him at the end of his life, I need to remind myself that there was a time when he was active in the outdoors, taking bike-camping trips and hiking the beautiful Pacific Northwest woods.

I liked dancing with him at my wedding. It seemed symbolic, traditional, a ritual that signified my participation in some ancient customs of transition. Like the transition from my father's home to my husband's home, which in my case was pure symbol, since I'd only lived with Dad a total of about a year from the time I was 4 and my parents divorced. My struggle between wanting to see myself as a rebel and wanting to embrace what little tradition and ritual I can goes on. Yet MY dance with MY father at MY wedding felt personal and right, and I'm glad he was able to share it with me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed