The Christmas season for my family includes 3 days of celebration. My mom has dibs on Christmas, my in-laws get Christmas Eve, and my dad and stepmother--a non-Jew and a non-Christian--have hosted "Christmas Adam" every December 23rd for 30 years.

Last year was Dad's last Christmas Adam, and it was the first year that my sister Amanda and I happened to tell Carol, our stepmother, that it was our favorite holiday event. Christmas Adam was always mellow, low-key, delicious, warm. The year before, when Dad was not very well, Amanda and I made it clear that we needed Christmas Adam to happen, and we'd be happy to do all the preparations. That was a sad year because Dad was exhausted from multiple hospitalizations in the months before and from the compounded problems those hospitalizations both discovered and created.

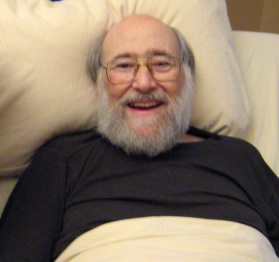

Last year might have been a little sad, but it was more truly a celebration. Per the Latin root of celebration, it was "numerous, thronged, and renowned." Everyone was present who could be, and we took a series of family photos centered on Dad in his hospital bed in the dining room. He was happy. And he was dying. He lived nineteen more days.

This year, we "bravely" went forward by recreating all the necessary elements of Christmas Adam: an evening gathering, multiple orders of our favorite antipasto plate from a local restaurant, cookies galore, a big pile of presents for the children and tokens passed between their parents. The antipasto was augmented by simple dinner items. As in years past but not last year, we sat at the table and ate too much.

What we didn't do is acknowledge the big hole, the space Dad filled. We didn't do or say anything special or formal or ritual or spontaneous. Carol did buy some of the almond bark Dad liked. She made sure to put it on a separate plate from the peppermint bark because Dad wouldn't have liked them to mingle. She mentioned him a couple other times, and I heard her, and I nodded, and I said nothing more. None of us took the opportunity to toast or tell stories or cry in the corner. I hugged Carol and Adam, my half-brother and the namesake of the event, longer than usual, trying to silently communicate something I couldn't figure out how to say.

So in a way, we succeeded, and in a way, we blew it. Amanda and I--especially Amanda--put a lot of energy into other ritual moments in the past year, and it felt to me like celebrating Christmas Adam was a triumph of joy over sorrow. Actually, in the weeks leading up to the 23rd, I envisioned a sad and subdued version, and after indulging my imagination for a while, I decided that I would just live in the present and not anticipate what sadness might come. While I ended up feeling pretty good about the evening, I also ended up feeling the loss of moment, the lack of a decisive, overt marking of the first year without Dad.

We'll have another chance, though, lots of other chances. Amanda read something in a grief resource that pointed out that just because we didn't figure out a special ritual this year, or this day, doesn't mean we couldn't recover from that in the future. It doesn't mean we couldn't say to each other and to Carol that we wished it had been different. It doesn't mean that next Christmas Adam can't be different, more attended to and aware and ritualistic.

It means there was a silence, and there will be another chance to make our noise joyfully.

Last year was Dad's last Christmas Adam, and it was the first year that my sister Amanda and I happened to tell Carol, our stepmother, that it was our favorite holiday event. Christmas Adam was always mellow, low-key, delicious, warm. The year before, when Dad was not very well, Amanda and I made it clear that we needed Christmas Adam to happen, and we'd be happy to do all the preparations. That was a sad year because Dad was exhausted from multiple hospitalizations in the months before and from the compounded problems those hospitalizations both discovered and created.

Last year might have been a little sad, but it was more truly a celebration. Per the Latin root of celebration, it was "numerous, thronged, and renowned." Everyone was present who could be, and we took a series of family photos centered on Dad in his hospital bed in the dining room. He was happy. And he was dying. He lived nineteen more days.

This year, we "bravely" went forward by recreating all the necessary elements of Christmas Adam: an evening gathering, multiple orders of our favorite antipasto plate from a local restaurant, cookies galore, a big pile of presents for the children and tokens passed between their parents. The antipasto was augmented by simple dinner items. As in years past but not last year, we sat at the table and ate too much.

What we didn't do is acknowledge the big hole, the space Dad filled. We didn't do or say anything special or formal or ritual or spontaneous. Carol did buy some of the almond bark Dad liked. She made sure to put it on a separate plate from the peppermint bark because Dad wouldn't have liked them to mingle. She mentioned him a couple other times, and I heard her, and I nodded, and I said nothing more. None of us took the opportunity to toast or tell stories or cry in the corner. I hugged Carol and Adam, my half-brother and the namesake of the event, longer than usual, trying to silently communicate something I couldn't figure out how to say.

So in a way, we succeeded, and in a way, we blew it. Amanda and I--especially Amanda--put a lot of energy into other ritual moments in the past year, and it felt to me like celebrating Christmas Adam was a triumph of joy over sorrow. Actually, in the weeks leading up to the 23rd, I envisioned a sad and subdued version, and after indulging my imagination for a while, I decided that I would just live in the present and not anticipate what sadness might come. While I ended up feeling pretty good about the evening, I also ended up feeling the loss of moment, the lack of a decisive, overt marking of the first year without Dad.

We'll have another chance, though, lots of other chances. Amanda read something in a grief resource that pointed out that just because we didn't figure out a special ritual this year, or this day, doesn't mean we couldn't recover from that in the future. It doesn't mean we couldn't say to each other and to Carol that we wished it had been different. It doesn't mean that next Christmas Adam can't be different, more attended to and aware and ritualistic.

It means there was a silence, and there will be another chance to make our noise joyfully.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed