So I wrote Mar a letter, the first and last one I ever wrote her. And whatever else was wrapped in paper under the tree, the gift she gave us was to get out of bed one more time, and laugh and smile with us.

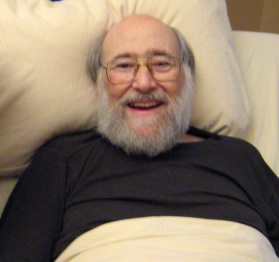

I wrote Dad a letter for my last gift to him. I reprint it here in its entirety.

December 23, 2012

Dear Dad--

To paraphrase Amanda, the difference between taking care of you and taking care of a baby is that the baby doesn't say “Thank you” when you say goodbye.

I don't know when I'll have to say goodbye to you for good, so I wanted to say thank YOU now for taking care of ME.

Thank you for picking me up when I was little. I forgive you for stopping when I got too big.

Thank you for singing to me, for reading to me, and for playing the recorder. Thank you for taking me to movies, plays, concerts, and dances. Your deep love of the arts inspires me.

Thank you for taking wonderful photos of me and other family members.

Thank you for trying to get me to stop eating lettuce and grapes to support farm workers' rights. Thank you for joining the March on Washington. Your liberal values have helped guide me through life.

Thank you for supporting me, emotionally and financially, even when you saw little of me. All around, of the all the divorces I've heard of, yours seems to have done the best at maintaining civility and love amongst a family divided.

Thank you for your good humor and tolerance for change, and your amazing adaptability. You have helped me understand how to communicate the important things better. You've taught me how to age with grace.

Thank you for letting me take care of you during this amazing time, this gift of days and hours. I will always treasure the relationship we've created out of what the Dalai Lama calls “the daily experience of hardship.”

I feel there is no way to say what I need to say completely enough, so I'm grateful I can share yet more time and love with you.

Love, Pearl

Postscript: After Christmas Adam, I noticed the letter lying around, unopened. I didn't know what to say to Dad about that, and there were a lot of other pressing matters (like hydration, and positioning, and bed-bath scheduling and hospice personnel visits). Eventually, Carol and Amanda mentioned that he was nervous about what was in the letter, and that he wanted me to read it to him. I did, and he smiled and thanked me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed